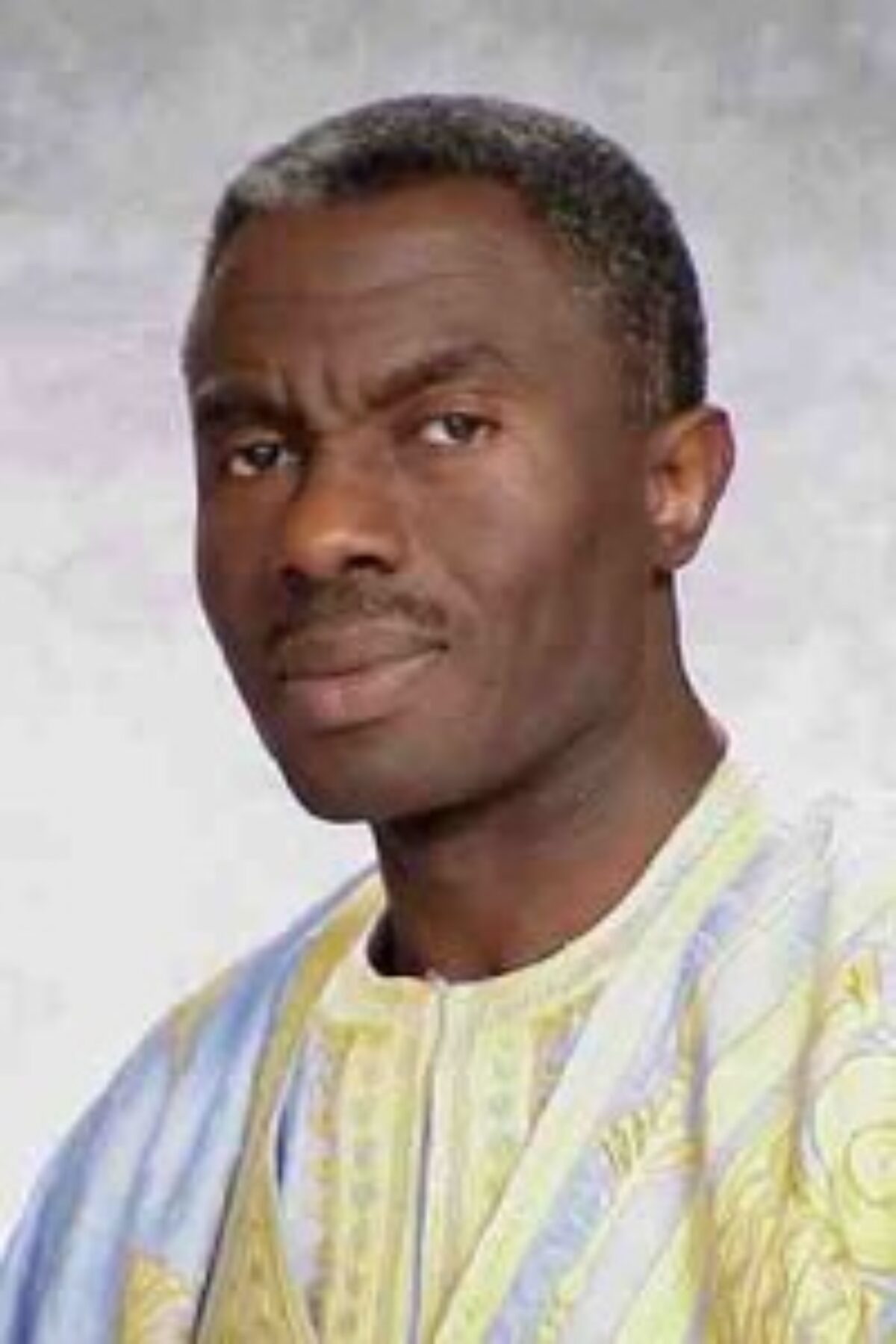

Dr. Ousman Gajigo

According to recent news report, the Gambian National Army (GNA) will engage in a commercial agricultural investment with a foreign investor, a US agricultural company called AGCO. This is a monumental mistake by the government. Only if one is confused about the proper role of the military and oblivious to the danger created by this institution’s encroachment in commercial activities would one consider this venture a source of positive development.

Let there be no doubt that the agricultural sector is arguably the most important sector in the country. It is also the case the agricultural sector has not experienced much productivity gain since independence. To address the lack of productivity in the agricultural sector, several measures are needed. Some of the solutions can only be addressed by the government, while others are best tackled by private investors.

The government’s role centers on the provision of sector-specific infrastructure whose public good nature makes it difficult to be adequately provided by the private sector. In fact, private investments are likely to be contingent on such infrastructural investments by the public sector. At the end of the day, the sector’s progress would greatly depend on private investments, be they foreign or domestic.

What is absolutely not needed to bring development in agriculture, however, is the involvement of the military. This institution is ill-positioned to be an agent of progress in agriculture, either by itself or in collaboration with other investors. There are many reasons for this that should be obvious.

First of all, this is not the role of the military. The primary responsibility of the military is defending the territorial integrity of the country from outside threats. If the military has so much excess manpower or time that it is even considering such a major undertaking, this is a good indication that perhaps the military is not needed at all in The Gambia. If that is the case, then the best course of action is to abolish the military rather than having it engage in important activities in which it has no expertise.

After all, there is no reason why the country should spend almost D700 million annually on a useless military when our hospitals are without adequate medicine, schools are without sufficient trained science teachers, police officers are underpaid and a large part of our infrastructure is dilapidated.

There are other risks to having the military encroach in areas beyond where it is needed or useful. As already pointed out by others such as Madi Jobarteh, having the military go beyond its core responsibility brings all sorts of major problems that become impossible to disentangle.

Once the military has its foot in one commercial sector, it quickly moves to another. After all, if you allow the military to undertake commercial investments in agriculture, how would you argue against its involvement in manufacturing or tourism?

Once the door is opened, the military becomes too entrenched and interwoven in the economy like a malignant cancer. History has shown that such a situation has not turned out well for countries who had the misfortune to allow that to happen.

This business venture also does not speak well for the private partner. An investor such as AGCO would be engaging in such a venture with an eye towards circumventing regulations and responsibilities that other investors would be bound by, as well as inappropriately profiting from working with a partner whose costs are already borne by the government.

For instance, any member of the military that works in the venture would mean AGCO having access to free or highly subsidized labor and endless other privileges. Instead of developing the sector, such a venture would allow the company to use the military to crowd-out legitimate and rule-abiding agricultural investors that are fully paying for their costs. These legitimate investors, some of whom would be local firms, would no longer be able to compete on a level playing field. How is such a situation supposed to advance the agricultural sector?

It should be clear that AGCO does not have legitimate reasons for this venture. A foreign investor would look for a local partner that brings some knowledge or expertise in an investment. The army has no such expertise.

Being Yahya Jammeh’s shepherds or farmhands at Kanilai does not count. What should be obvious to anyone in the government is that AGCO sees its collaboration with the army as a means to maximizing its profits by improperly getting access to resources without paying fair prices. This alone should be disqualifying.

It is also important to point out that a legitimate serious investor would go through the proper channels such as the Gambia Investment and Export Promotion Agency (GIEPA). Not only did AGCO fail to go through GIEPA for this venture, it bypassed the Public Private Partnership unit at the Ministry of Finance, which is responsible for overseeing all PPP investments.

Furthermore, this AGOC-army venture did not go through the office of the Permanent Secretary at the Office of the President responsible for investment. So, how was it possible for the government to determine that public interest was served in this venture?

The key government figure in this venture, CDS Massanneh Kinteh, did us a favor by unwittingly demonstrating how ill-equipped the military is for such an endeavor. Showing either mind-blowing incompetence or willfully insulting the collective intelligence of the country, CDS Kinteh claimed that the participation of the military in the commercial venture is a constitutional requirement. If the CDS is so confused about the constitutional role of the military, what are the chances that he knows how to oversee such a transaction that is so far outside of his competencies, such as they are. What shenanigans were done to consummate such an irresponsible deal?

It is not an idle question to ask what underhanded activities may have taken place for such a venture to be launched. After all, AGCO has a track record of bribery and corruption. For instance, United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) fined the company $20 million in civil and criminal penalties after being found guilty of bribery in 2009.

The government of Denmark has fined the company $630,000 for bribery when the company violated UN sanctions. Any serious government would require that such a company go through proper channels and insists that the relevant government institutions overseeing public private partnerships carry out a thorough due diligence.

I was initially going to conclude this article by urging President Barrow to surround himself with better advisors if he thinks this venture is a good idea as the press reports claim. And that any advisor who had told him that this venture was a good idea should lose his or her position. However, that would assume we have a president who is not clueless and who has a sound judgement. But we are not that fortunate. So, I join others in appealing to the National Assembly to do their duty and subject this venture to a level of scrutiny it deserves.

Ousman Gajigo is an economist. He has held positions with the African Development Bank, the UN, the World Bank and Columbia University. He holds a PhD in development economics. He is currently an international consultant and also runs a farm in The Gambia.