By: Alexis Petridis

Bleak beats soundtrack an album of smart introspection as the rapper ponders his Gambian heritage and ‘wild west’ home

This year may well have been the toughest in history for a new artist to break through to mainstream success. It’s not merely the lack of gigs, festivals and club nights, or the sense of the promotional machine running at a reduced pace; it’s the feeling that the year’s unprecedented upheavals prompted fans to cleave to the familiar, finding comfort in nostalgia rather than seek out the new. The list of biggest-selling albums in 2020 is packed with releases that came out last year, two years or even four decades ago.

Clearly, Pa Salieu neglected to read the memo about this state of affairs. The release of his first mixtape crowns 12 months that would be remarkable by anyone’s standards. This time last year, he was the author of a handful of tracks and freestyles that had attracted plenty of YouTube views, but also plenty of peevish remarks in the comments about his alleged similarity to J Hus, another MC of Gambian descent. He was also recovering from being shot in the head in a drive-by attack outside a pub in his adopted home town of Coventry, or, as he calls it on Informa, “C-O-V, hashtag city of violence”.

By his own account, the latter incident acted as a spur: his January breakout hit Frontline started a torrent of rapturously received new tracks and collaborations: one, Betty, was Radio 1’s record of the week for three weeks in a row. Along the way he has collaborated with FKA twigs and Burberry.

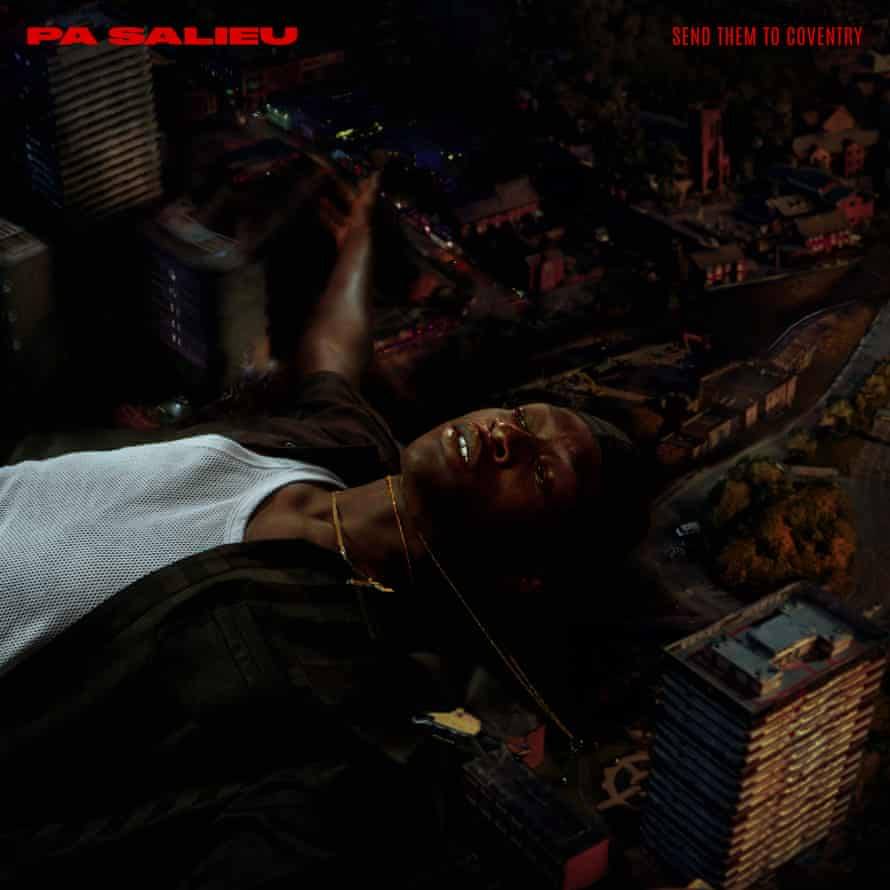

He ends the year as Britain’s hottest new rapper, turning up on the cover of magazines that don’t generally feature rising UK hip-hop talent. On the cover of Send Them to Coventry, he appears giant-sized, reclining over a city that the album’s contents depict in terms so unsparing they make the Specials’ Concrete Jungle, their own grim ode to their home town, seem like a quaint expression of civic pride. “My name is Pa, I’m from Hillside,” opens Block Boy, “bust gun, dodge slugs, got touched, skipped death.”

Salieu has pulled off his breakthrough largely through carving out a musical space entirely of his own in a crowded market. You can see where the comparisons to J Hus have come from – there’s a distinct note of Afroswing about the beats – but Salieu’s music is largely devoid of Hus’s lush melodicism. The most obviously hooky of his 2020 singles, Bang Out, which sampled Japan’s Ghosts, is absent; the closest he leans to pop comes on More People, with its 80s soft-rock synths, and Energy, decked out with limber bass and vocals from UK soul singer Mahalia. Instead, he taps into the ominous atmospherics of grime and the minimalism of dancehall, the latter particularly noticeable on No Warnin’, featuring a vocal from Trinidad’s Boy Boy.

On Frontline and Flip, Repeat, Auto-Tuned vocals are marooned over a bleak landscape of ghostly, high synth lines, minor chords, murky bass tones and dubby echo; Betty has an insidiously catchy chorus, but it’s set against a backdrop that’s creepy and muted, the electronics churning in the distance.

The overall effect is to spotlight Salieu’s voice, which is fantastic and, like the music, seems to exist in a space between genres, his delivery slipping naturally between rap flow and dancehall toast, between understatement and imposing bellow. His lyrics lurch between thoughtful considerations of his African heritage and its place in what he calls “the wild west”, and grimly unflinching reportage from the “frontline” of Hillfields.

The macho swagger of the gun talk is undercut, lent a hollow, desperate tone, both by the music and his willingness to shift from boasts to sudden moments of stark clarity and introspection: “All I’ve known is patience”; “I never saw my power”.

It’s smart, original, raw and occasionally cathartic listening. Perhaps the success of a track like My Family – a raucous, unrepentantly aggressive collaboration with BackRoad Gee, another UK rapper audibly in touch with their African heritage – does have something to do with the events of the last eight months: rather than escapism, it feels like a release of pent-up emotions. But Send Them to Coventry sounds like it would have been successful at any time, regardless of extraneous circumstances: it’s too fresh and inventive to ignore.

Source: The Guardian