By Yunus S Saliu

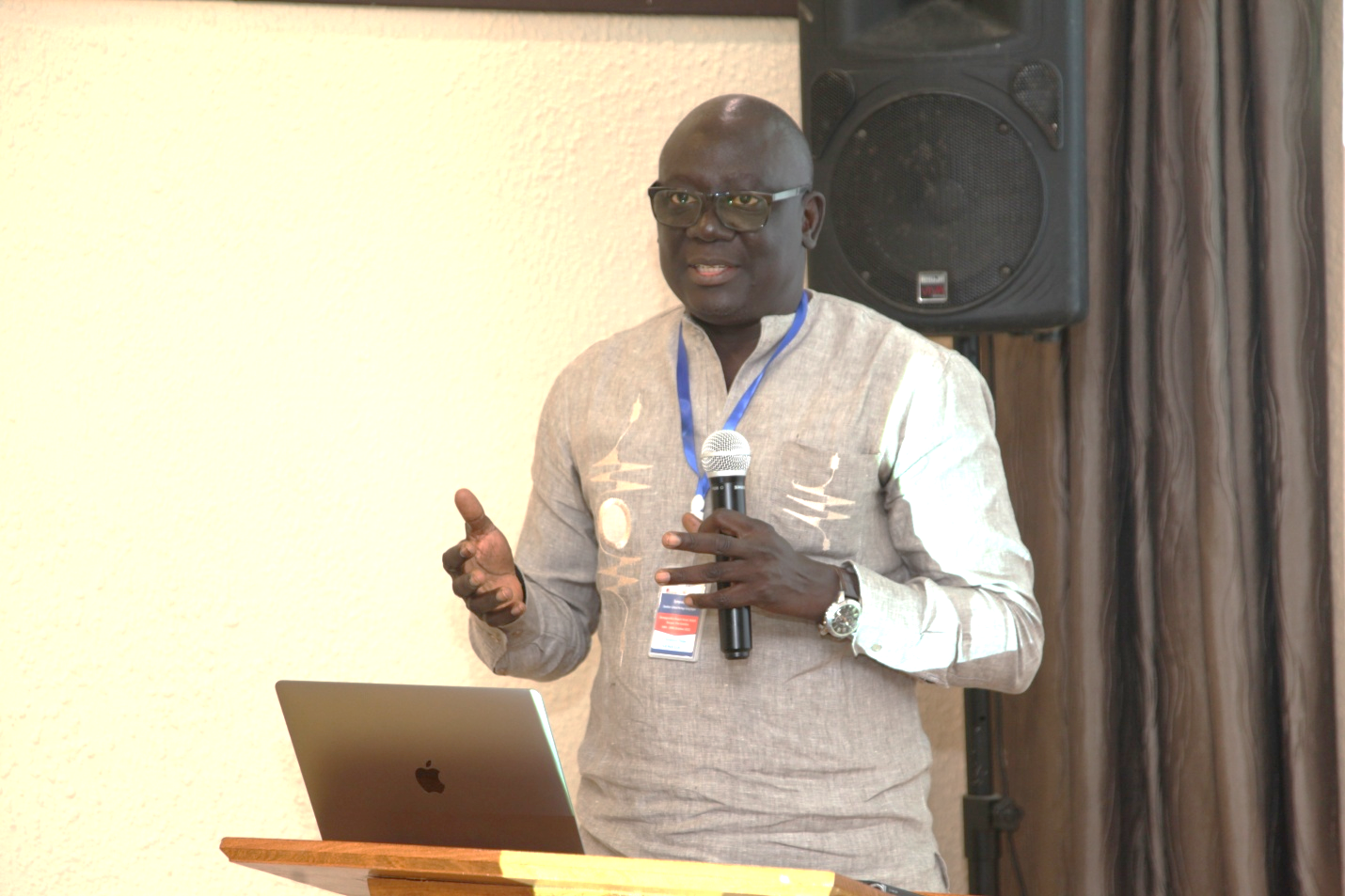

In his presentation on the toxic archives and the nation building in the Senegambia: Lessons from IFAN Cheikh Anta Diop, Ibrahima Thiaw of the URICA-ETHOS, Laboratoire d’Archeologie has proclaimed that oral tradition is an art capable of narrating difficult histories in ways that diffuse tensions and build a bridge within the diverse audience.

In his research paper presented at the just concluded oral history international symposium titled Gambian Cultural Heritage goes digital, he noted that African presence in the colonial archives is often involuntary and, consequently African voices are muted and their bodies imprisoned.

“Although,” he explained, “colonial archives talk about African life experience, Africans generally “has no ownership of the archives. Black bodies are quite often represented in the colonial archives in inhumane and undignified conditions without their consent. As such those representations exude pain that challenges our humanity generation after generation.”

Further elaborating on the toxicity of colonial archives, he said Africans’ relations with the assemblages of objects and memories that form archives are not neutral. “They are qualified through language and must be contextualized politically and historically. And the Era of high-speed accessibility and risk of seeing violence reproduce in common digital commons.”

In addition to it is the need for dialogue, reparative justice, and a commitment to truth-telling for balanced reparative memorialization.

Mr Thiaw reminded the listeners of Institut Francais D’Afrique noire (IFAN) that it was founded in 1936 and was a network of museums and research centers throughout the French colonial empire in West Africa and the mission was to inventory and collect information on sub-Saharan African people and resources to inform and guide colonial policies on the management of people and resources.

After independence in the 1960s, IFAN became the Senegal center the name was changed from ‘Institut français d’Afrique noire’ to ‘Institut Fondamental d’Afrique noire’ on the eve of the World Festival of Negro Art in 1966. In 1967 IFAN hosted the Panafrican Archaeological Congress and in 1986 it becomes IFAN Cheikh Anta Diop, renamed after one of its most radical decolonial scholar.

In the era of digitization, he said for the common people of the former French colonial empire in West Africa, IFAN appears as a huge graveyard of objects acquired according to methods that are the antithesis of ethics, in the context of colonial and sometimes even post-colonial violence.

“Our collections are a product of those fraught relationships that dispossessed African people of their cultural heritage and use them to represent and construct an image of the African colonial subject and his or her environment imagined without their consent. IFAN, like European museums and institutes engaged in research in colonial territories, seem to ignore its heavy emotional and symbolic burden,” he explained in his paper.

Digital technologies, according to him, offer possibilities for virtual and symbolic restitution of the collections and knowledge stolen from the populations by the colonizer, while how to mitigate the pain and violence embedded in the archives.

He went further in the paper that the structural problems of research and the management of sites, monuments, and archaeological collections are largely due to the colonial scientific heritage still perniciously nested in African contemporary practices.

However, Thiaw hoped that this will opens new possibilities for community engagement for greater democratization and access to archaeological knowledge.

In his conclusion, he said Archaeology has always been attentive to social movements, many of which contribute to reconfiguring its paradigms. The current moment calls for reparative history to attend to the demands and aspirations of historically dehumanized and disenfranchised people.

“Therefore we must unpack the legacies of slavery and colonialism embedded in the archives to tackle problems of the citizenry, nationhood, and social justice in the present and use digitalization with care to repair past wrongs and to make historical production more multi-vocal, interactive, and reflexive. Let’s use archives for education, as a catalyst for change within society but also to imagine a better way of being and living (utopia),” he urged listeners at the symposium.