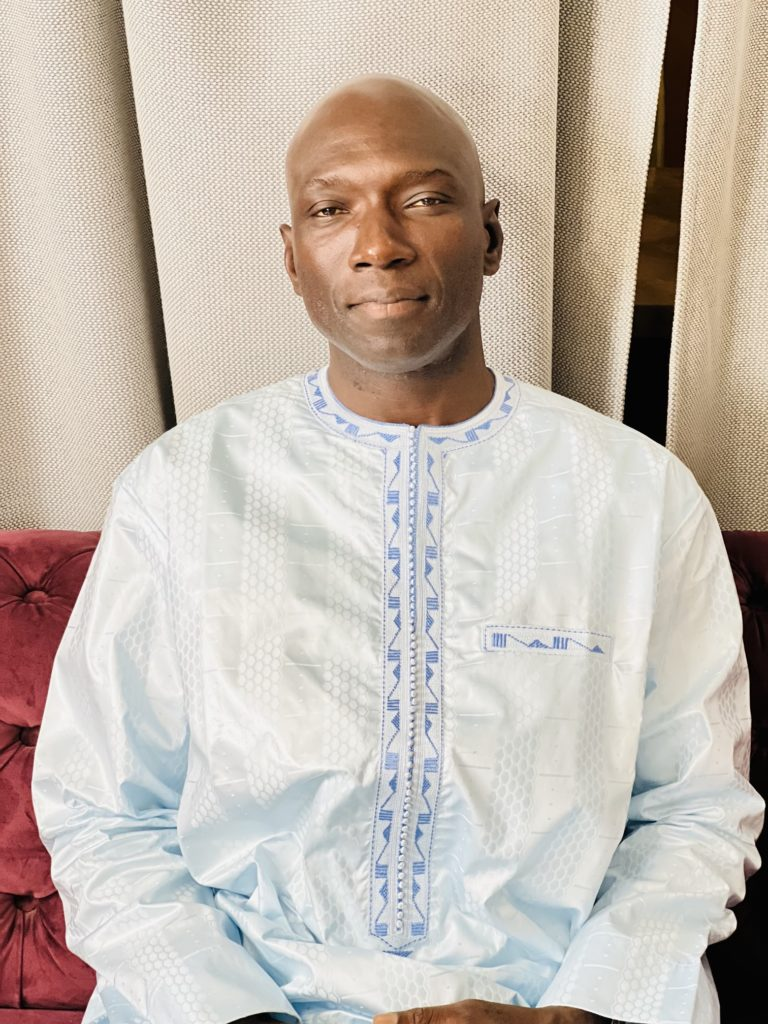

Dr. Ousman Gajigo

A few days ago, I wrote an article concerning the asset recycling agreement that the government has made with Africa 50. In the days since I wrote that article, I have become increasingly worried not so such about the inherent characteristics of this type of funding arrangement but rather about the government’s ability and will to faithfully implement its part. To be clearagain, there is nothing fundamentally wrong about asset recycling as a means of funding new infrastructure. Indeed, its potential is immense. Rather, my concern is based on the poor track record of the Barrow government and its general limited capacity. Indeed, subsequent attempts at clarification by the Ministers of Finance and of Works have only compounded my worries.

There is yet more to learn about the Senegambia Bridge asset recycling deal. Minister Keita was insistent in his press conference last weekend that the concession is yet to be signed. Under most circumstances, the concession agreement would be the document that contains all important and pertinent details about such an arrangement. However, a great deal has already been agreed between the government and Africa50. Specifically, for a head of terms agreement, a remarkably high number of important details seem to be agreed upon such as the value of the bridge (US$ 100 million), ownership structure of the special purpose vehicle, the target internal rate of return (15%) and the length of the concession (25 years). With such important details already set in stone, what other consequential issues are left?

A major area that we should worry about is how well the Barrow government will manage the use of the US $100 million if this deal goes through. My concern is not mere unfounded speculation. Let’s consider a very recent situation with this very government just on the eve of the last election in 2021. In 2021, BP paid the government US$ 35 million for not following through on an agreement to drill an exploratory well in an off-shore oil block. This money was an upfront lump-sum payment to the government. Within the government at the time, there was an initial understanding that this unexpected windfall amount would be spent on infrastructure.

What actually transpired was different. The-then Minister of Finance Mambury Njie prepared a supplementary budget where the funds were quickly dispersed over many items that had beenalready been budgeted and some even had financing arrangements already in place. One of the projects that received a significant amount of that amount was the Banjul Roadsproject, which already had a financing arrangement that was negotiated and signed. Some of the funds did not even go into infrastructure. It was clear that politics and short-term considerations were the main determining factors in how that amount was used.

So while the government could have indicated beforehand that the US$ 35 million would be spent on infrastructure projects, what ended up transpiring afterwards was different. The reality is that there is no shortage of infrastructure projects in the country but they are not equal in terms of priority. A government whose spending decisions are largely driven by considerations other than long-term development can ostensibly allocate money to projects that are low in the order of priority. Or we could have a situation where politically connected contractors have their payment schedules moved up even though agreed payment plans have been are already in place.

The current Minister of Finance, Mr. Keita also kept harping on the point that this deal is not a “sale” or “mortgage”. When people raise concerns about this transaction and end up with a characterization that appears inaccurate to him, the proper response is to provide greater clarification. Repeating incessantly that the deal is a “monetization” does not contribute to clarification. What determines whether this deal becomes a debt or not depends less on the monetized value but more on what structures are in place to ensure that the US$100 million is spent on an infrastructure that is at least as valuable as the Senegambia bridge. It is the lack of comfort in this government’s ability to ensure that outcome that fuels much concern about this transaction.

Minister Keita also kept on reminding us that Africa50 is a “development” institution. Yes, it is a fact that the Africa50 was established by the African Development Bank and African countries in 2012. But its deals are commercial in nature. It does not provide any concessional financing. There is no grant element in this particular deal. Even the African Development Bank prices its private sector investments on market terms. The point here is that no one is implying that Africa50 is taking advantage of the government in this particular deal. The fiduciary responsibility of the officials of Africa50 is to ensure the best deal they can get for that institution, which is perfectly legitimate. At the same time, the officials of the country are duty-bound to ensure that they are looking after the long-term interests of the country, irrespective of what type of institutions they deal with. They should not lower their guard and sense of duty simply because they are dealing with the African Development Bank or World Bank or the International Monetary Fund.

An agreement can look great on paper but there will be no development impact when there is poor execution. As the first asset recycling deal in the country, it is quite important that all aspects of it are managed well. For one, it will have a significant demonstration effect not just locally but within the sub-region. Secondly, the relevant officials need to demonstrate that theyappreciate the level of responsibility involved. After all, by the time this deal will be completely implemented, these individualswill all be long gone from the government. But the effects of their actions – good or bad – will be felt for generations.